Blog

Heavy Metal Pollution and Stillbirth in Bangladesh

Heavy Metal Pollution and Stillbirth in Bangladesh | Christlee Doris Elmera | September 1, 2023

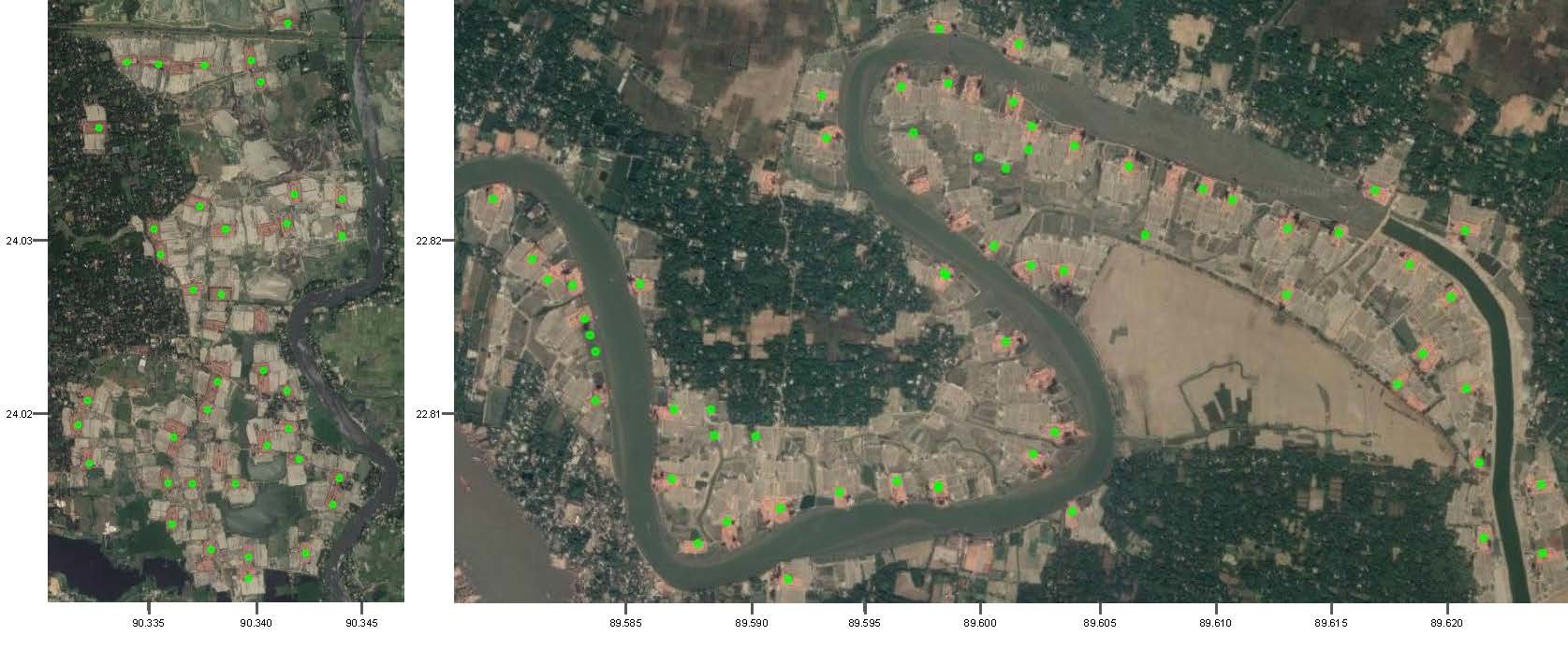

I have greatly cherished the opportunity to contribute to the study “Investigating infectious and environmental etiologies of Stillbirth in Bangladesh”, as a predoctoral fellow, over the past two years alongside Ashley Styczynsky, Allison Sherris, Seth Hoffman, our colleagues at icddr,b (International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh) and many other people. This project aims to understand the contribution of heavy metal exposure to the high rates of stillbirths in the Faridpur district of Bangladesh.

My first trip to Faridpur, in 2021, focused on piloting our environmental survey questions. Conducting in-person pilots in Bangladesh provided insights into the questions' feasibility. For example, we once thought it was appropriate to ask: "What is your water source?", all to realize, through the pilot, that respondents had different water sources for drinking, cooking, and cleaning. Once all questionnaires were piloted and revised, collection started.

I went back to Faridpur in winter 2022. The main goal of this trip was to experience and evaluate the environmental survey process in person. This turned out to be a logistically challenging and emotionally heavy process. The lack of formal addresses made finding households particularly arduous. This led to increased appreciation for the team conducting the surveys under these circumstances while still providing high quality work.

It is important to recognize the sensitive nature of our research question. The approach is a matched case-control study so while we visited households that had a healthy baby, we also visited households that were actively grieving the loss of their child. There is a feeling of powerlessness in not yet being able to provide answers to families eager to understand what may have contributed to their loss. This solidified the understanding that attached to each of the data points collected, there is a real human being, an entire family and sincere pain.

The visit was also marked by a tour of the Faridpur district hospital’s maternity ward. While there, I was allowed to attend a live vaginal birth of triplets. While the ward is equipped only with the absolute essentials in terms of medical instruments, it is able to carry out these complicated procedures due to the accumulated exposure to delicate cases. The physician expertly removed the last of the triplets that the mother was too fatigued to push out. It was something that would be rare to observe in the cushiest of hospitals.

This visit has marked me and will forever influence my research ethics. There are many things to take into consideration when conducting research. While many believe that a good research question is difficult to formulate, it can be even more challenging to investigate. One must be conscious of feasibility, logistics, partnerships and most importantly, the very real people behind each ID.

Epidemiology behind the alarmingly high rate of stillbirths in Bangladesh

Bangladesh Stillbirth (Placental) Metagenomics | Seth Hoffman | June 26, 2023

Stillbirths are a major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries. In Bangladesh, the stillbirth rate is 25.4 per 1000 births, which is among the highest in the world. Studies have shown that maternal infections can be a major factor in stillbirths, accounting for up to 18% of cases.

In order to reduce the number of stillbirths in Bangladesh, it is important to identify and treat maternal infections. This can be done through early and regular antenatal care. We are currently investigating the role of infectious diseases in stillbirths in rural areas of Bangladesh. The study is using shotgun metagenomic sequencing to analyze placental tissues from stillborn babies to look for infections that might be occurring without the mother or her doctors knowing about it – shotgun metagenomic sequencing is a technique that can be used to identify all the microorganisms present in a sample. The results of this study will help to shed light on the causes of stillbirths in Bangladesh and will inform the development of interventions to prevent them.

We are working with our colleagues at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b).

Esther Hoffman, Seth Hoffman, Burgess Gbelee, Patrick Sonah

Assessing Salmonella Typhi Contamination of Water in Urban Settings of Liberia

Fighting Typhoid in Liberia: Using Bacteriophage to Improve Surveillance Equity | Seth Hoffman | June 12, 2023

Typhoid fever, a disease that has haunted humanity for centuries, continues to claim lives in our modern world. Recent estimates by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation reveal that in 2017 alone, 116,000 individuals lost their lives to typhoid, with children under 15 years old accounting for 56% of the cases. This alarming statistic highlights the urgent need for action, especially in low- and middle-income countries like Liberia, where the estimated burden of typhoid remains high.

Understanding the Problem in Liberia: Liberia’s capital, Monrovia, has witnessed significant population growth in recent years. However, data on typhoid burden and transmission in the country are sorely lacking. Previous studies have indicated high contamination of drinking water sources in Monrovia with fecal bacteria, suggesting a potential avenue for typhoid transmission. To address this gap, in partnership with National Public Health Institute of Liberia, we are using typhoid-specific bacteriophage (bacteriophage: a virus that eats bacteria) surveillance to establish baseline data on water source contamination, including municipal piped water and hand pump wells. This innovative approach has proven successful in Nepal and Bangladesh and holds promise for Liberia.

The Importance of Baseline Data: By analyzing the prevalence of typhoid in common water sources, we aim to uncover the underlying mechanisms driving typhoid transmission in urban Liberia. Traditional methods of environmental surveillance, such as culture and PCR, have limitations in accurately confirming positive results and interpreting negative ones. Typhoid-phage surveillance, however, offers a low-cost, sensitive, and specific alternative for detecting S. Typhi. This valuable data will not only aid policymakers and stakeholders in resource allocation, such as vaccine distribution and water supply improvement but also serve as a catalyst for similar initiatives in other regions lacking crucial typhoid burden data.

Typhoid fever continues to pose a significant threat, particularly in low- and middle-income countries like Liberia. Our work aims to address the gaps in understanding typhoid transmission by employing innovative typhoid-phage surveillance methods to establish baseline data on water source contamination. This information will empower policymakers and stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding resource allocation and intervention strategies. Additionally, the success of this approach in Liberia may inspire its adoption in other regions lacking essential typhoid burden data. Through our collective efforts, we strive to combat typhoid fever, protect vulnerable populations, and create a healthier future for all.

Identifying the most significant contributors to child blood lead levels (BLL) in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Lead Intervention : Continuing work on Reducing Lead Exposure | Christlee Elmera | March 30, 2023

I have greatly valued the opportunity to work on the Lead initiative, as a predoctoral fellow, over the past two years alongside Jenna Forsyth and Steve Luby. The Initiative aims to determine and reduce the sources of lead exposure in South Asia. A major aspect of this initiative is the continuation of the work previously done in Bangladesh around lead in turmeric: Lead Intervention: Improving health, intelligence and economic growth by reducing lead exposure.

My first trip to Bangladesh took place in 2022. It was shortened due to the pandemic. We were setting up three different research projects, taking place in four different sites: “ Identifying the most significant contributors to child blood lead levels in Dhaka, Bangladesh”, “Effectiveness of nation-wide lead-tainted turmeric reduction intervention in reducing lead exposure among pregnant women and children” and “Investigating Infectious and Environmental Etiologies of Stillbirths in Bangladesh”. My time there was full of logistical conversations, pilots, supply inventory, and troubleshooting. We were setting the stage for months of data collection. Most of our data in Dhaka was collected by Fall of 2022. We were getting ready to make sense of it.

I traveled to Bangladesh again in January of 2023. The main objective of this trip was to gain a qualitative understanding of the data previously collected in Dhaka. The team and I traveled to various industries of interest around Dhaka to better understand their modes of operation and comprehend their potential contribution to lead in their environment. We interviewed workers, nearby shops, and neighbors. We encountered incredibly friendly people that greatly contributed to our understanding of their environment. We have also encountered tight-lipped, cautious business owners that suspected we might be journalists. The team was skilled in navigating these uncomfortable situations.

This trip was also filled with memorable personal moments. One of which was attending a natural birth…of triplets. I got to share touching moments with the team: shopping trips, baby showers, and so much laughter. Although short lived, the camaraderie was proof of the Luby lab’s long standing relationship with the team at Icddr,b.

COVID-19: Fractional Dose COVID Study

Is half a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine booster dose enough? | Joelle Rosser | March 21, 2023

The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in a boom of scientific progress and collaboration but it also highlighted the stark inequalities in healthcare access globally. Global disparities could not have been more apparent than with vaccine distribution worldwide. By January 2022, people living in the United States and Europe were being offered SARS-CoV-2 vaccine boosters while health systems in the majority of low and middle income countries (LMICs) were still grappling with getting their populations vaccinated with even single dose. Given the robust immune response demonstrated in the early clinical trials of the Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines, even with half or one-third the dose of the approved vaccines, it seemed reasonable to suspect that a fractional booster dose of a highly efficacious SARS-CoV-2 vaccine might be just as good as a full dose and could double or triple vaccine supply in low resource settings. Additionally, a fractional dose might have the added benefit of fewer side effects, which could in turn also decrease vaccine hesitancy.

This prompted the call from Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) for research programs to carry out vaccine booster trials comparing the immune response and side effect profile of individuals boosted with fractional versus full SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Stanford answered this call by entering into a collaboration with the Sabin Vaccine Institute, Aga Khan University Hospital in Pakistan and FioCruz in Campo Grande Brazil to design a multi-arm study to evaluate fractional doses of the Pfizer and AstraZeneca SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccines.

In July 2022, Dr Rosser went down to Brazil to help launch the trial in Brazil. The Brazil study site has now recruited approximately 1500 participants across 26 different study arms (divided based on which vaccine participants originally received in their primary series and which vaccine dose they were randomized to in the trial) and have now completed the first month of follow-up. The Pakistan study site is also up and running despite a series of challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme floods over the past year. All participants will be followed for 6 months after booster vaccination.

Although COVID-19 may have faded into the backdrop for many people in the U.S. over the past year, the fight to provide efficacious vaccine boosters worldwide continues. The results of this study will provide robust clinical data on fractional SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccines to help guide those ongoing efforts.

Methane Emissions: Spring 2023 | Chungheon Shin | March 21, 2023

We have been evaluating ten vendors' proposals to procure one incubator and one methanotrophic bioreactor that meets our design criteria and budget. We are currently selecting two manufacturers to check the final spec and PNIDs (piping and instrumentation diagrams).

See below for all Project Team Members!

HCF Liberia: Comparing Hospital Hand Hygiene in Liberia: Soap, Alcohol, and Hypochlorite

Improving Hand Hygiene in Liberia: Spring 2021 | Lucy Tantum | May 31, 2021

The trip from SFO to Monrovia, Liberia takes a little over 24 hours. It’s a long flight, but after over a year of waiting to return to Liberia to resume our fieldwork, it felt like no time at all.

In spring 2020, we completed a baseline assessment for our study of hand hygiene infrastructure and practices at rural Liberian hospitals. Then, the Covid-19 pandemic hit, so we worked from home to design hand hygiene interventions, staying in touch with Liberian collaborators from afar.

However, there is often no good substitute for in-person fieldwork and meetings — this is true anywhere, but particularly so in Liberia where internet infrastructure is iffy at best. So, in April, as soon as we were vaccinated and had approval to travel, project lead Ronan Arthur and I booked flights to Monrovia. Goals of the trip were to meet with government and other local collaborators; train our field enumerator team; and plan and implement a pilot of our hand hygiene intervention.

Though Ronan and I were eager to visit the study hospitals and begin our pilot, we first had to spend some time in Monrovia, leading trainings for our Liberia-based enumerator team. Much of this training focused on hand hygiene observations, where enumerators record data on health worker hand hygiene practices during patient care. These hand hygiene observations are straightforward in theory but can quickly become complex in reality. During training, we used video tools, demonstrated patient care interactions, and fielded lots of questions about hypothetical hand hygiene situations until enumerators could record data confidently and accurately.

While in Monrovia we also met with our Liberian government partners, including the Minister of Health, the Director-General of the National Public Health Institute of Liberia, and senior infection control personnel. In these meetings, we discussed our work and learned about ongoing hospital infection control and Ebola prevention efforts. By working with government stakeholders, we hope to align our project with their goals and inform policy through our findings.

Once enumerators were trained and government partners briefed, pilot implementation could begin. I traveled with the enumerator team to Bong Mines Hospital, located about a 2-hour drive inland from Monrovia, to start baseline data collection for the pilot. Gaps in hand hygiene infrastructure at Bong Mines were clear: The hospital had water available in buckets, but there was no running water and few hand sanitizer dispensers. There were remnants of past hand hygiene interventions put in place by other organizations, but many of these interventions had not been sustained.

To avoid a similar fate for our project, we are focusing on interventions that are low-cost, local, and easily integrated into existing hospital structures. One potentially sustainable intervention is hospital-based production of hand sanitizer. While I was at Bong Mines, Ronan visited Phebe Hospital, another study site which has an existing hand sanitizer production program. Ronan found that, while Phebe’s production site was up and running, hand sanitizer was sitting in storage instead of being distributed on hospital wards. During our pilot intervention at Phebe, we will devise a plan to improve the distribution system for hand sanitizer in the hospital and explore strategies to sustain production in the long term.

Now that our project pilot is underway, we will closely monitor uptake of our interventions, iterating and modifying our approach as needed. In a few months, we will conclude the pilot and implement a full-scale intervention. I’m grateful that this trip afforded the opportunity to work with our enumerator team in-person and further our collaborations with local partners, and I can’t wait to return to Liberia soon.

Read Prior Related Blog: Reflections during a pandemic | Ronan Arthur | November 24, 2020 >>

SEAP: Surveillance for Enteric Fever in Asia Project and

Typhoid Fever | Chris LeBoa | April 6, 2021

Over the last five years, the Luby Lab has been involved with developing new surveillance tools for estimating the burden of Typhoid fever in Southeast Asia and evaluating the effectiveness of a new typhoid conjugate vaccine. Typhoid fever, a food- and water-borne disease that before the advent of antibiotics killed 25% of the people it infected (including Leland Stanford Jr., for whom our university is named), still infects millions and kills upwards of 100,000 people annually [1]. In 2018, the World Health Organization fast-tracked the approval of the Typhi Conjugate Vaccine (TCV). This vaccine is the first to be approved for children as young as 9 months and gives people a robust immune response for at least five years [2]. The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) and national governments are now trying to understand how to conduct surveillance, so they can then focus on vaccine rollout, can understand how well the TCV vaccine works, and can understand possible safety concerns when the vaccine is rolled out through mass vaccination campaigns.

I first became involved with the Luby Lab’s work on typhoid through the Surveillance of Enteric Fever in Asia Project (SEAP). This multi-country hybrid surveillance study proposes to understand the true incidence of enteric fever across India, Nepal and Bangladesh. A hybrid surveillance study combines the number of blood culture positive Typhi and Paratyphi cases that are reported at hospital and laboratory sites with data from a healthcare utilization survey so that the true number of cases that exist in an area can be estimated.

Our team wanted not only to understand who was getting sick with typhoid and reporting to hospitals, but to see if we could develop tools for detecting the disease-causing Salmonella Typhi bacterium from local water sources. This environmental surveillance approach could possibly become a cheaper way to detect areas with ongoing Salmonella Typhi transmission, even following a vaccination program. With our colleagues Dr. Jivan Shakya and Sneha Shresta from Dhulikhel Hospital, Stanford colleagues Jason Andrews, Alex Yu, Kristen Aeimjoy, and I set up monthly environmental surveillance along the five rivers running through the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal. This process was definitely a learning journey. Each month of sampling presented new challenges, from getting to our sampling locations during the monsoon months, to having to adapt the filtering methods used on the very turbid samples. Our ongoing study has shown a nearly 40% positivity rate for Salmonella Typhi. We have observed Salmonella Typhi contamination in agricultural areas up to 10 kilometers downstream of Kathmandu. We have also witnessed people washing vegetables in the contaminated river locations in preparation for market, a possible exposure pathway for Typhi to spread within the city’s population. Though a University of Washington coordination group, we are working alongside collaborators from around the world to create best practices of typhoidal environmental surveillance for use by other researchers and public health departments.

Our lab also works to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the first mass-vaccination rollout of the Typhoid TCV vaccine. In 2018 the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC) in Navi Mumbai, India, decided to vaccinate its whole population with the newly approved TCV vaccine over two phases. Together with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the India National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases (NICED), and the World Health Organization (WHO), former Luby Lab member Lily Horng set up a surveillance system in hospitals and laboratories across Navi Mumbai. This surveillance system proposed to understand the number of S. Typhi and Paratyphi cases that appeared in vaccinated and unvaccinated populations over the following two and half years. With funding from the Gates Foundation, we also were able to set up a safety evaluation of this vaccine, looking for possible adverse reactions participants faced after vaccination. With our collaborators at the CDC, we have been able to calculate the TCV vaccine to be safe and more than 80% effective. We are in the process with working with NICED to sequence the genomes of typhoid isolates collected during this study to better understand the antimicrobial resistance patterns of Salmonella Typhi from across the city. We are working to disseminate our vaccine effectiveness findings to stakeholders within the Indian government and to the World Vaccine Alliance, as they decide policies for incorporating TCV into normal childhood vaccinations within India. As our work has been completely remote since March 2020, I have relied extensively on the support of our WHO India field team leaders Dr. Niniya Jayaprasad and Dr. Priyanka Borhade, to keep our surveillance sites safely operating when possible and to keep this work moving forward.

References

[1] Typhoid fever | WHO

[2] Efficacy and immunogenicity of a Vi-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine in the prevention of typhoid fever using a controlled human infection model of Salmonella Typhi: a randomised controlled, phase 2b trial. | Jin C, Gibani MM, Moore M, Juel HB, Jones E, Meiring J, Harris V, Gardner J, Nebykova A, Kerridge SA, Hill J, Thomaides-Brears H, Blohmke CJ, Yu LM, Angus B, Pollard AJ. Lancet. 2017 Dec 02; 390(10111):2472-2480.

Assessing brick kilns number, location and use in Bangladesh

Laying the foundation for cleaner brick manufacturing | Nina Brooks | March 12, 2021

When I first started working on brick manufacturing with Dr. Luby and Debashish Biswas (from our partner icddr,b), and Luby Lab alum Alex Yu, I thought we were getting ready to deliver an energy efficiency intervention for brick kilns in Bangladesh. Five years have gone by, but I am very excited to say that we are now starting to develop the interventions. We’ll carefully pilot and update the intervention based on our experience. Then, we will implement a large-scale randomized controlled trial and rigorously evaluate the impact to generate evidence-based policy recommendations for improving kilns across all of Bangladesh.

This time has been crucial for laying the foundation of our current research plans. We realized that before we could start implementing interventions, we needed to generate more evidence on the consequences of how bricks are currently made. We also needed to expand on our existing partnerships. To do this, we conducted a longitudinal health outcomes study in Mirzapur in collaboration with icddr,b and the Child Health Research Foundation. We conducted surveys, measured health outcomes, and monitored air pollution over two seasons: when brick kilns operate (winter) and when they do not (summer and monsoon). But crucially, we also needed to know where the brick kilns were located, so we could link air pollution from kilns to the communities we were working in.

To pinpoint the locations of brick kilns, we collaborated with the SustainLab and worked really closely with computer science students Jihyeon Lee and Fahim Tajwar. Together, we developed a deep learning approach that identifies where brick kilns are located in satellite imagery and produce a database of the locations of all brick kilns Bangladesh. Not only did this effort give us the kiln locations we needed to quantify the health impacts of living near kilns, it also allowed us to look at how effective existing regulations governing the brick industry are. This research is now forthcoming at the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Through this research, we are able to empirically show how kilns are responsible for a disproportionate amount of air pollution that affects the people living downwind from them causing increased risk of respiratory disease and the current regulatory approaches to reduce the negative impacts of kilns are failing the people of Bangladesh. This work also highlights the need to clean up brick manufacturing – so that it generates less air pollution and contributes less to climate change.

Now, with support from the King Climate Action Initiative at J-PAL and the Stanford Impact Labs, we can finally put our vision into action. This month we’ll begin an in-depth qualitative investigation among kiln owners and managers that will shed light on what they think the biggest barriers to clean technology adoption are. We will also collect a series of technical measurements of kiln operation and energy efficiency performance. This information will inform the interventions we will pilot during the next brick production season. Ultimately, this careful, systematic process is essential for building the evidence, support, and collaborations to deliver a successful intervention.

COVID-19: Essential Health Services in Zambia

Impacts of COVID-19 on essential health services and how this relates to climate change | Joelle Rosser | February 26, 2021

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, my first thought that how this disaster would have health consequences reaching far beyond the immediate SARS-CoV-2 infections. I also thought about how understanding our response to this disaster was relevant to thinking about building health resiliency in the face of climate change and emerging infectious diseases.

The COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic threatens to undermine delivery of essential health services and set back important gains made in all health sectors. The potential impact ranges from maternal mortality, childhood vaccinations and malnutrition programs to control of other infectious diseases like HIV, TB, and malaria. Furthermore, many of the world’s already vulnerable populations will be hit hardest by these indirect impacts. For example, World Food Program has estimated that the number of people in LMIC’s affected by acute hunger may be as high as 265 million people by the end of 2020, a doubling from the expected 135 million people anticipated pre-COVID-19. Sadly, children are by far the most vulnerable group. Malnutrition as a child can have life-long health impacts. Furthermore, programs to support child nutrition have been hit by the pandemic. This includes school closures and consequent cessation of school meal programs, halting of mass nutrition campaigns or routine infant weigh checks at health centers. And like with other disasters, the impacts go far beyond this single issue. Various models have predicted that excess deaths due to the interruption of medical services for TB, HIV, and malaria alone could far exceed excess deaths due to SARS-CoV-2 infections in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Indirect health impacts of this pandemic can be caused by multiple mechanisms. An outbreak, particularly of a deadly and highly transmissible infection like SARS-CoV-2, generates fear and diverts attention and resources away from more routine but critical services. People may be afraid to go to the hospital. Medication supply chains can be interrupted. Illness caused by another treatable disease may go unrecognized and erroneously attributed to the outbreak. Transportation which may be difficult at baseline becomes even more of a hurdle and sometimes impossible. Moreover, the economic shock from the disaster can have enormous impacts on nutrition, mental health, and overall access to care.

Ebola as an early teacher:

This phenomenon of one disaster having a ripple effect through multiple, seemingly unrelated sectors is familiar. Past experiences with infectious disease outbreaks and natural disasters have demonstrated that the indirect health effects due to the breakdown of basic health services can equal or even exceed the morbidity and mortality directly attributable to the immediate disaster. The 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa is a poignant example. During that outbreak, routine healthcare utilization was estimated to decrease by about half due to fear of Ebola transmission. Decreased HIV, TB, and malaria services of that magnitude are estimated to have resulted in more excess deaths due to those infectious diseases than due to Ebola infections themselves. The interruption of vaccine programs like measles and polio can result in outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases and undermine infectious disease elimination efforts.

The impacts also go beyond the spread of other infectious diseases. Decreased antenatal care and hospital births can have serious impacts on maternal and neonatal mortality, as was also noted during the Ebola epidemic. An overwhelmed health system may not be able to provide other emergency services including surgical or intensive care services, particularly in places with low physician densities or limited medical supplies. Halted or delayed preventative services such as cancer screenings can also have delayed but significant impacts. Such services may not rebound enough to make up for missed prevention opportunities or delayed diagnoses.

What we are working on:

We are working with partners in Zambia (including rising young Zambia researcher, Christabel Phiri, pictured here) to quantify the infectious disease and maternal-child health service disruptions at University Teaching Hospital (UTH) in Lusaka, Zambia early in the COVID-19 pandemic. UTH is the country’s largest infectious disease and maternal health hospital which makes it a key hospital to study. Identifying the services most affected by the pandemic can be immediately used to guide policies and resources to bolster the health system in the current crisis, both in Zambia and across Sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, these measures are key to building accurate mathematical models to predict the indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic for larger scale mitigation strategies.

Why this matters beyond the current COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons for climate change

The lessons gained from studying these indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are critical as we face the even bigger task of mitigating the impacts of climate change. Given climate change, globalization, and population growth, pandemics are expected to become more frequent. SARS, Ebola, and Nipah viruses were already emerging onto the scene before the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In our lifetime we will undoubtedly continue to face these and other infectious diseases of pandemic potential. Changing environmental conditions are also changing the density and distribution of various other zoonotic (transmitted by animals) and vector-borne (transmitted by insects) infections. West Nile Virus has spread across the United States in recent years. Dengue virus has increased dramatically worldwide and environmental conditions in the U.S. are becoming increasingly favorable for the mosquitos that spread dengue virus. An epidemic of Zika virus caused large numbers of cases of microcephaly in Brazil, followed shortly by the re-emergence of deadly yellow fever virus in urban areas of Brazil that had been free of yellow fever for nearly a decade. The emergence of these viruses is intimately linked with changing environmental conditions. And this is to say nothing of other natural disasters like droughts, floods, wildfires, and heat waves that are becoming increasingly frequent and severe due to climate change.

Maintaining essential health infrastructure during infectious disease outbreaks and other natural disasters, particularly when these disasters are happening in multiple places around the world simultaneously, is critical to health. This pandemic sets the precedent for how we respond to future outbreaks and natural disasters. Using this pandemic as an opportunity to identify the areas of the healthcare system most vulnerable to disruptions is critical to planning for and mitigating the health impacts of climate change.

Reflections on risk communication and the meaning of “unsafe” water | Allie Sherris | February 3, 2021

I first met Carmen last year at her home in rural Tulare County, CA. I was testing her well for contamination as part of a research project on domestic well water quality in partnership with the Community Water Center. Two weeks later, I called to tell her that her water was unsafe. We found nitrate, commonly derived from fertilizer, at concentrations over twice the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL), as well as an agrochemical called DBCP at detectable levels.

Delivering this news to Carmen and other study participants has led me to a reckoning of the word “unsafe”. The dichotomy defined by MCL cutoffs is wildly insufficient to answer questions such as “Can I cook with my tap water?” or “Can my children drink it?” Our community partners and I need to communicate the risks honestly and clearly, providing participants with enough information to make informed decisions for their health and the health of their families.

But risk communication is a risky business. Overstating the danger of contamination might lead to psychological harm and unnecessary costly avoidance measures like exclusive reliance on bottled water. Minimizing the danger could perpetuate harmful exposure. Complicating this balance is the co-occurrence of different contaminants, often with distinct long- and short-term health consequences.

As academics, we often quantify risk by citing the literature. Exposure to nitrate above 10 mg/L vs <0.5 mg/L, we might say, was associated with a 52% increase in odds of colon cancer in a study by McElroy et al. 2008. This information is important to the progression of science, perhaps, but it does little to answer Carmen’s questions.

Regulators and other public-facing groups often quantify risk by citing MCLs. Yet MCLs are generally established for specific populations and health outcomes. The nitrate MCL (10 mg/L as N-nitrogen) was designed to prevent methemoglobinemia in infants, or “blue baby syndrome”, but does not consider other health outcomes or vulnerable populations. What’s more, a binary cutoff makes little intuitive sense. If 10 mg/L nitrate is unsafe for use in infant formula, should 9.9 mg/L be considered “safe”?

Appropriate risk communication requires distilling scientific literature and regulatory guidelines into understandable, actionable messages. But the honest answers to questions like Carmen’s are often “we don’t know” or “it depends.” We may understand the risks of nitrate to infants, but the literature on pregnancy impacts is nascent. The “safe” levels for long-term cancer risks are likewise poorly understood. We certainly don’t know whether combined exposure to multiple contaminants in tap water might compound or modify health outcomes.

I hope that my research can help to provide answers to these questions. In a study nearing publication, I found that exposure to nitrate during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of preterm birth, even at concentrations below regulatory limits. Perhaps this kind of research, in combination with that of other scholars, can lead to improved regulation and a clearer assessment of risk. But I also recognize that this pathway to change is slow. In the short-term, I am listening to the urgent questions, concerns, and expertise of those with unsafe water, and doing my best to work towards appropriate answers and solutions.

Note: Pseudonyms have been used to protect participant privacy.

Luby Lab Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Goals | Jessica Grembi | December 2, 2020

Today the Luby Lab met to discuss the formation of our lab goals around diversity, equity, and inclusion. Because of our lab’s engagement with international collaborators from many different countries, we have a unique perspective on this topic that is different from many other Stanford labs. The discussion was organized by lab members Allie Sherris and Latifah Hamzah, whose prior work on the topic resulted in a draft of six lab values related to diversity, equity, and inclusion (in no particular order):

Value 1. Recruit and support members of underrepresented groups in science.

Value 2. Support the professional development of international collaborators and make sure our relationships are not transactional.

Value 3. Acknowledge and confront the way that our internalized, interpersonal, and institutional levels of power, history (particularly colonialism), and politics affect our work.

Value 4. Center our actions around the core value of public health as a social justice imperative, founded on the idea that all people are worthy of healthy growth and development. Commit to anti-racism by having a critical perspective of our own actions and policies, and practice open and accessible science.

Value 5. Intolerance, racism, discrimination, and sexual harassment are not tolerated.

Value 6. Be supportive of each other and hear all of our perspectives.

The discussion, held over Zoom, included a larger group discussion based on preliminary ideas for each value, followed by small group brainstorming sessions for actionable goals for each.

I participated in a small group that brainstormed goals and action items for Values 1 & 6 and below I share some of the ideas that we came up with or that were offered in the larger group discussion:

Value 1. Recruit and support members of underrepresented groups in science.

a. Learn more about, and commit to participate in, programs already in place to mentor under-represented minorities applying to Stanford within our respective departments (Civil & Environmental Engineering; School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Sciences; or School of Medicine).

b. Cite work from Black and Indigenous People of Color and international scholars in our research.

c. Create a handbook of lab processes and expectations around research, grad school, applying to the lab, etc. This effort will help people from diverse backgrounds whose direct network doesn’t include anyone that has been to graduate school. Also, many of our international colleagues request help and advice on applying to grad school in the U.S. so this document could combine existing resources into one place and can be a living document that is updated as new questions are raised.

d. Encourage and support international collaborators to attend and present at lab meeting as a professional development opportunity. This could take the form of co-presenting with them, providing a forum for them to present/practice a talk for an upcoming conference, or lead a brainstorming session for an upcoming grant proposal. We can state in our lab processes documentation that individuals are encouraged to volunteer to present at lab meeting and indicate who to contact to request a time slot.

Value 6. Be supportive of each other and hear all of our perspectives.

a. Make it our intentional practice to validate comments and input provided at lab meetings or other forums.

b. Reach out to lab meeting attendees who are less verbal and ask what they see as barriers to participation.

c. Experiment with methods to ‘popcorn’ (or hand off the microphone) to another lab member after speaking. For example, after I speak, I would offer, “Allie, do you have anything to add?” We can be intentional to ‘hand off the mic’ to individuals who speak less.

d. Explicitly state that active participation is an expectation (in the expectations section of the lab processes document that is being produced), and emphasize that everyone’s opinion is important because all lab members bring a unique perspective to the table. In later discussion it was raised that not everyone might feel comfortable speaking up in lab meeting, so this document should acknowledge that active participation can take many forms:

1. Sharing thoughts/ideas/opinions verbally during lab meeting.

2. Sending comments to presenter after lab meeting.

3. Arranging a one-on-one meeting with presenter to provide feedback, seek clarification, or offer other thoughts/ideas.

e. Follow up with people who have attended a few lab meetings, but then stopped coming. There could be reasons for this that are unrelated to our inclusion (e.g., they were interested in our work but realized their interests were better matched with another group), but we might learn about practices that we could improve on to promote inclusion.

f. Look beyond Stanford and think about ways to include our international collaborators in lab meetings to ensure their voice is being. Specifically, we can move lab meeting to evening to accommodate our international colleague’s attendance.

g. Assign an official note-taker for each lab meeting to ensure all voices are captured and can be reflected upon later; and to provide a means that the presenter can remain engaged with the audience instead of worrying about taking notes.

h. Make it a lab practice for everyone (or a few people per lab meeting?) to provide written feedback to the presenter about any aspect of the presentation (content, flow, presentation style, tone, etc.). Steve routinely does this by asking students in class to provide feedback on what went well and what can be improved in a class session. We could model our feedback in this manner (2-3 things that worked/should be sustained and 2-3 things that could be improved).

The next steps in the process will be to identify priorities for action and assign roles and responsibilities. Latifah has volunteered to spearhead the lab handbook initiative and will create a working group to help contribute to a first draft. Allie will work to draft the lab’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Mission Statement. Ongoing informal conversations will continue over the next month while the following priority action items are being worked on:

* Learn more about under-represented minority mentoring opportunities within our departments.

* Look at what existing resources are available for a lab training on anti-racism and colonialism, explicitly any focused on global health research.

* Follow up with individuals who have stopped coming to lab meeting to inquire about how we might improve our inclusivity.

* Establish a formal mechanism for note taking & providing written feedback after lab meetings.

At the conclusion of today’s meeting we committed to the following action items effective immediately:

* Establishing future lab meeting times that are convenient for international collaborators related to the project being presented.

* Validating comments and input from all lab members during lab meetings.

If there’s one thing to know about working with Dr. Luby, it’s that he loves to set goals and then work methodically towards achieving them. I’m certain that once our goals are fully fleshed out, we will develop a strategic action plan and make strides towards accomplishing them!

HCF Liberia: Comparing Hospital Hand Hygiene in Liberia: Soap, Alcohol, and Hypochlorite

Reflections during a pandemic | Ronan Arthur | November 24, 2020

For a global health researcher, sitting behind a keyboard in a makeshift home office in the United States without physical access to the institution that supports them or to the field team they partner with or to the location where they strive to effectuate small improvements in health represents a significant change. We are used to the buzzing, bustling, and hustling of cities in low-income countries; the complex network of government officials, foreign researchers, non-profit types, and the often selfless nurses and doctors that influence the health system in which we too engage; the small, troubling sights and experiences that represent wide, trans-national disparities in access to healthcare and preventable illnesses and death.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had knock-on effects on the daily life of nearly everyone on the planet, so it's perhaps no wonder that we are no exception. In Liberia, where we work, we have been interested to understand the knock-on effects of the pandemic on health, trust, and beliefs. We saw during the Ebola epidemic in 2014 that Ebola had a large impact on the country, and not just on those infected or on those employed in healthcare. People stopped shaking hands; funerals done in culturally important ways were forbidden; markets and schools were canceled; checkpoints and blockades were set up; and a riot in the capital resulted in a fatality of a minor. Health indicators of all kinds dropped as the system was overwhelmed by Ebola, and patients would not go to clinics for routine services.

When COVID-19 became a massive international crisis, before it had been given the name, our team was at work in Liberia to improve hand hygiene practices in rural hospitals. As the alarm bells rang louder, we realized the importance and relevance of our study. As with Ebola, preventing hospital-based transmission would be one of the top priorities of the response effort in Liberia, and our project was in a position to help with that. As we geared up to complete our baseline survey of hospital hand hygiene practices and systems, I was ordered to evacuate from Liberia. I protested, citing the importance of our work, but was overruled. I flew out the next weekend, on the same plane that, unbeknownst to me, had just delivered a government official that would be the first case of COVID-19 in Liberia. I was sick three days later, presumably from that plane. I lost my sense of taste and smell, and had significant trouble breathing for two weeks. I would struggle with fatigue for another two months.

I have been behind a desk ever since. Our implementing partners in Liberia have continued our work in my absence with their own delays due to COVID-19, including strikes at major hospitals and restrictions on travel. We added an additional piece of research to track knowledge, attitudes, and practices on COVID-19 over time. We knew about and have researched the importance of trust during Ebola, and we sought to measure it for COVID-19. How would the pandemic affect trust, beliefs, and routine services at hospitals and clinics? Our team has finished their baseline work at hospitals, interviewing over 70 hospital workers, conducting observations and spot-checks at 7 hospitals, and conducted over 600 telephone surveys.

COVID-19 may not have had as drastic an impact on Liberia as did Ebola or as drastic an impact as COVID-19 has had on the United States. But low-income countries remain the most vulnerable to pandemics and other biological and health risks. Tracking what happens next in Liberia with our survey work and strengthening hospital hand hygiene systems will improve our knowledge and understanding of these crises and prepare us for future ones.

And, as for me, I'll just have to get used to the desk and the Whatsapp conversations that have replaced feet on the ground. For now.

PPE Testing | Ashley Styczynski | November 16, 2020

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Luby lab came together to brainstorm ideas of how we could contribute to addressing this global health crisis. With a keen awareness of the unique challenges in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), we decided to take on a project around shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers in LMICs. Our aim was to provide evidence to inform the creation and assessment of locally-available protective equipment, when none of the recommended options are available, and develop locally-appropriate recommendations for conservation of available PPE through extended use and reuse.

We joined forces with the Prakash lab as well as partners from UCSF, UC Berkeley, UC Irvine, and Tata Institute of Fundamental Research to identify high-priority areas that, if answered, would immediately empower frontline HCWs in resource-limited settings globally to protect themselves:

1) We reviewed the literature to identify methods of PPE decontamination effective against SARS-CoV-2 that could be adapted for low-resource settings;

2) We evaluated filtration efficiency of various cloth materials using optimized testing methods;

3) We investigated the impact of decontamination strategies on the filtration performance of surgical masks and N95 respirators;

4) And, we assessed the impact of sanitizing agents on glove integrity using a water leak test.

Through our joint efforts, we created infographics and a website on appropriate use and existing decontamination methods for PPE based on peer-reviewed literature. We developed a database of filtration efficiencies for various cloth materials that informed an ongoing community mask trial in Bangladesh. For decontamination, we demonstrated that even after multiple rounds of washing with soap and water, surgical masks perform significantly better than cloth masks. We also optimized the design of UV-C units for decontamination of N95 respirators and facilitated their construction and implementation in several countries. Furthermore, we demonstrated that latex and nitrile gloves can be safely decontaminated, allowing for extended use.

Although PPE shortages are likely to continue, our research has shown that evidence-based strategies can be effectively implemented in the setting of resource limitations to maximize the usability and reusability of existing PPE supplies. This, in turn, can have a positive environmental impact by minimizing generation of biomedical waste.

Improving health, intelligence and economic growth by reducing lead exposure

Reflections during a pandemic: Progress toward reducing lead in turmeric | Jenna Forsyth | October 16, 2020

I’ve done a lot of reflecting lately, spurred on by the pandemic, devastating wildfires, and the fact that 2020 is an election year. I’ve reflected broadly about the state of the world, and how now, more than ever, we need leaders who respect scientific evidence. By the same token, we need scientists to generate and disseminate this evidence so it can have an impact. To this end, I’ve reflected about my own scientific pursuits, and the fact that, after 6 years of research we are seeing positive change toward reducing lead exposure in Bangladesh.

I came to Stanford in 2014 because I wanted to work toward solving important problems. I knew Professor Luby would be an excellent advisor and mentor and that the E-IPER program would allow me to pursue applied research. Initially, I assumed that I would continue my work in water and sanitation that I’d begun in 2010 when I was working toward my master’s degree in engineering at the University of Washington. However, during one of our early advising meetings, Professor Luby shared data from a cohort in rural Bangladesh exhibiting higher-than-expected blood lead levels. Immediately, I immersed myself in this data. Before I knew it, my dissertation revolved entirely around lead. Over the course of my PhD, my team at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (iccdr,b) and I were able to identify turmeric adulterated with lead chromate as a major source of lead exposure.

Although I arrived at Stanford with impatient optimism, eager to dive into solutions, this is the first year that has been fully focused on solutions. We have seen some promising early signs that we are on track to reduce lead exposure. In late 2019, our team published two scientific articles and associated press releases published by Stanford and icddr,b describing the issue of lead in turmeric and its contribution to human lead exposure. Within days of disseminating this information, the Bangladesh Food Safety Authority (BFSA) called our team, concerned about the issue and wanting to take action. Our team assisted the BFSA in the development and distribution of 50,000 posters educating the public on the topic. The BFSA publicly fined 2 sellers and confiscated nearly 1 ton of lead-tainted turmeric at the major market in Dhaka. We monitored turmeric lead concentrations at that same market before and after the news release and related events. We found that in fall 2019, nearly 50% of 201 samples contained lead, compared to less than 5% of 157 samples in early 2020. These initial findings are promising but such lead reductions may not be sustained if the systemic drivers of lead chromate adulteration aren’t addressed. So, we are also working with turmeric producers and suppliers to develop post-harvest process improvements that will ensure higher quality turmeric and disincentivize lead chromate addition in the long-term.

I am amazed by the dedication of our team in Bangladesh to work on this issue even amidst a pandemic. As we begin to re-commence field data collection after a 6-month pause due to COVID-19, we do so with a renewed sense of the importance of the problem in light of global events, and with hopes that Government of Bangladesh will continue to take our evidence as seriously as they did in 2019.

Evaluating the role of vertical transmission of antimicrobial resistance in neonatal sepsis

Research Challenges During COVID-19 | Ashley Styczynski | September 17, 2020

After a 4-month COVID hiatus, we have almost completed enrollment of mothers and newborns for the study evaluating perinatal transmission of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Bangladesh. Now that we have SARS-CoV-2 to contend with, we have had to adapt to a new way of working to keep our study team safe. This has meant providing personal protective equipment (PPE) and training on the use of PPE, collecting fewer samples to minimize people in the lab, and obtaining institutional approval from our local collaborators to resume data collection.

When I mention to my colleagues in the US that we have resumed data collection in Bangladesh, I am often met with dubious glances. “You are resuming your study in the midst of a pandemic, intentionally sending your study team into hospitals?” I’ve gotten these looks enough times that I’m prepared with a response before they verbalize the question. “My study team could not be dissuaded,” I say with a shrug. After all, the reality for my study team of living and working in a lower middle-income country is entirely different from ours.

It’s not all about salary. We were able to support the study team during the COVID hiatus. During our research pause, the study research physician continued to work in the hospital providing care for patients, often without PPE. As part of the study, we are providing PPE. When PPE is used correctly, risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 when entering hospitals can be greatly mitigated. I certainly depend on it when providing clinical care. The alternatives to working often include staying at home in cramped conditions, going to crowded markets, and depending on public transport, which are not exactly without their risks either. And while COVID is certainly circulating in these communities, many people continue to be affected by non-COVID etiologies, including life-threatening antibiotic-resistant infections. In fact, it was my study team who pointed out that our research is addressing an important problem, which is why we must keep going.

Despite the additional hurdles we’ve faced doing research during COVID, I’m glad that we’ve been able to move forward because – as my study team reminded me – AMR will be an ongoing problem facing humanity long after COVID is gone. Just because we are in the middle of a pandemic doesn’t mean that any of the other global health challenges have diminished. To the extent we can, we must persevere in supporting global health research efforts while mindfully taking measures to protect ourselves and our colleagues.

Research Challenges | Laura Kwong | August 25, 2020

As we prepare to resume fieldwork in the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, I reflect on our path to this point, our collaboration with humanitarian partners, and the value of multi-pronged data collection to overcome unexpected changes and shocks to the situation.

This research began when a master’s student at Stanford became interested in mapping the deforestation in Bangladesh that had accelerated after the arrival of nearly one million Rohingya refugees from Myanmar into Bangladesh. Quantifying the extent of a problem is an important step to taking action to address the problem. Dr. Steve Luby’s Lab at Stanford takes research farther by co-designing, piloting, refining, implementing, and evaluating interventions to improve child health and development. Instead of focusing on mapping the number of hectares that had been deforested, we took a step back to think about interventions that could prevent or reverse deforestation. Cooking without biomass was an obvious approach. Cooking without biomass could prevent or reduce a number of adverse environmental and human health impacts, including loss of forests and critical habitat for endangered Asian elephants, erosion and landslides, indoor air pollution, and harassment and violence that might occur while collecting wood. But how do you implement an intervention to provide refugees with clean fuel in a safe, sustainable fashion?

We quickly found that this distribution and training problem was one that UNHCR and the International Organization of Migration (through the SAFEPlus program) had started to address with their liquid propane gas (LPG) distribution program in the Rohingya camps nearly a year earlier. This program wasn’t a pilot that was testing LPG distribution in 100-200 households as we had planned. Rather, they were in the process of setting up monthly distribution to all ≈200,000 Rohingya households in the camp and many host community households. We quickly contacted the UNHCR LPG distribution and SAFEPlus program leads and worked together to develop a proposal for elrha, a UK-based funder that specifically funds research in humanitarian settings to improve life for internally displaced people, refugees, and stateless people.

After we received funding, we realized that we had to move very fast to conduct baseline surveys in households that were still waiting to receive their LPG vouchers. Families take their vouchers to LPG distribution centers where, on their first visit, they are provided with a LPG stove and 12-liter cylinder of LPG gas. On subsequent visits they bring their empty cylinder and exchange it for a full cylinder. The refill schedule is based on a household’s size, with larger households able to receive refills more frequently since they burn gas at a higher rate. The goal of the program is to provide refugees and some host community households with a continuous supply of LPG gas so they have no need to collect wood from the forest or to purchase firewood.

Relieved of the burden of implementing the intervention, we could focus on researching the human health and environmental implications of the program. Our research goals sought to quantify the impact of distributing LPG on respiratory disease; food security; sexual, physical, and verbal harassment and violence; household income; fuel expenditures; and time collecting fuel and cooking. We aimed to quantify how LPG distribution has impacted the rate of deforestation, elephant habitat loss, and landslide risks. With an eye to producing immediately actionable results, we also aimed to evaluate user satisfaction with distribution, LPG uptake and exclusive use, and the cost-effectiveness of the program. Our research goes far beyond a program evaluation to rigorously identifying a range of intervention impacts and assess the generalizability of these impacts.

We relied on face-to-face meetings and frequent, transparent email communication with the government of Bangladesh and camp and neighborhood leaders to rapidly obtain approval to work in the camps. It was crucial that the local research institution, the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) is a very well-respected public health research organization and hospital that is also an autonomous part of the government of Bangladesh. The ability of our staff to quickly develop friendly ties with neighborhood leaders was also key in obtaining information that had to be sent one text at a time given the limited phone and internet access in the camps (as of 25 August 2020 the ban was expected to be lifted in the near future).

The other potential difficulty we faced was identifying households that had not yet received LPG so we could select 600 of these households to participate in our household survey, monitoring of particulate matter <2.5 microns in diameter (PM2.5), and stove usage. It seems as though many of these household had not yet received LPG precisely because they were not well documented – they had some identity cards, but not the ones that would allow them to receive LPG. To overcome this hurdle, we turned to the neighborhood leaders. They knew each household in their neighborhood well enough to list those that did and did not have LPG.

During our baseline survey we surveyed 600 refugee households that had not yet received LPG, 600 refugee households that had already been using LPG for 24 months, and 200 host community households that had not yet received LPG. We have conducted PM2.5 monitoring in the household, outdoors, and with sensors carried by the female caregiver in the house. We also conducted multiple focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with women, men, adolescent boys and adolescent girls in order to understand their experiences obtaining different types of fuel, experiences and concerns regarding safety while obtaining fuel, and key informant interviews with donors of the project to better understand the context in which the program was implemented. During this time, our staff tirelessly hiked up and down the treeless hills packed with homes of tarp and bamboo, answered many questions posed by curious adults and children alike, and thanked many welcoming respondents for sharing their time and experiences.

No project is without its setbacks. Our setback came in the form of a global pandemic. In an effort to prevent coronavirus from entering the camps, the camps were closed to all but essential activities. The camp lockdown came just a few weeks before we planned to launch our endline survey. We halted our preparatory activities with the hope that the virus would stay out of the camp, and waited.

…and waited.

…and waited.

There was uncertainty about when the camp would re-open and the extent of the re-opening or when icddr,b would again allow staff into the field. We kept our lines of communication open and are checking in frequently. Rather unexpectedly, we have just received approval from icddr,b to resume our fieldwork and expect to receive permission from the Rohingya camp governance to re-enter the camps in September.

We are looking forward to conducting our endline household surveys and sensor measurements to understand the impact of the LPG intervention. Exposure to coronavirus and the camp lockdown likely affected some of the changes we were interested in assessing. Rates of respiratory illness may have been impacted by exposure to coronavirus, although it is difficult to tell how much the camp was impacted by coronavirus given extremely limited COVID-19 testing and reduced rates of healthcare-seeking in the camp. Food security and household income and expenditures may have been affected, because during the lockdown, refugees were unable to work as daily laborers outside the camp, received dry food on a monthly rather than a weekly basis, and may have had reduced access to fresh food markets. However, we expect that we will still be able to assess the impact of LPG distribution on respiratory illness by examining clinic records over the last several years. We will also gain some understanding of how LPG distribution impacted food security and fuel expenditures by using the baseline survey data. We are fortunate that the delay in data collection likely did not impact changes in indoor air pollution or rates of deforestation. We’re now doubly thankful that we planned into our study a variety of data collection methods, including qualitative and quantitative measures, to answer each of our research questions.

Stakeholders involved in the LPG distribution and SAFEPlus program are eager for our results as well. We are thankful that many of these stakeholders have worked together with us to facilitate the success our project has experienced thus far. Our strong partners have been fully engaged from the inception of the project, sharing their goals and concerns, and visions for how the data may be used. We look forward to sharing our results and facilitating the research uptake that is so important to bridging research results and research impact.